In fact, the only users who really enjoy the park are dogs. The empty fields at Fort Reno are great for letting dogs run free. The only problem is that it’s illegal. Dogs must be on a leash on NPS land. There is just nothing right with Fort Reno Park, is there?

Now, it’s easy to spitball amenities to fix the park, but Fort Reno is uniquely charged with history. There’s was a Civil War Fort and then a Black town bound up in its formation. Buried under the grass are vast possibilities to impregnate our lives with history. On the other hand, as more and more residents return to the district, we will really need useful parks.

So, how do you take this kind of site and interpret it while also making it a great urban place?

A recent project in Brooklyn shows us a few ways.

Strategy One: Put a frame on it

Take a look at the Weeksville Heritage Center, located in northeastern Brooklyn. Not so much of an open space as a corner of East New York, the site preserves five houses from a historical Black settlement. Most of Weeksville came down for projects during Urban Renewal, but a tiny portion remained, wedged laterally into a block.

Like Tenleytown, Weeksville was quite some distance away from the city (Brooklyn), but was later absorbed by urbanization. Unlike Tenleytown, none of the roads were converted into the grid, and few of the houses were. Tenleytown used to be two settlements: a largely White area near the Wisconsin-River intersection, and the Black town occupying what is now Fort Reno Park. Very little of both remains.

Weeksville was “rediscovered” in the 1960s by an extension class at the Pratt Institute. Residents were still floating around, but its history was unofficial and uncollected. In the same sense, Tenleytown was rediscovered in the 1970s, as the last people to remember it tried to collect their memories. Weeksville has been slowly doing the same for years.

Now, they’re part of the neighborhood, with the completion of an education center by Caples Jefferson Architects. An elegant, L-shaped building, it faces the city and puts up a great streetwall. It serves as a threshold between the wholly urban outside and the fragment of the rural inside. The new building mediates between old and new without disrupting the rhythm of the blocks.

Contrast this to the way Tenley Campus was handled. Even though the new building will be an improvement, the lawn on Tenley Circle will remain pretty dead. The HPRB asked to keep that area clear in order to to preserve the rural look the of Immaculata School, circa 1906. But an old building surrounded by a big lawn won’t look rural, it will look suburban. The contrast between old and new environments isn’t clear enough to say anything; nothing calls out the history.

Like the Getty Villa, Caples Jefferson’s renovation calls attention to big artifacts through architecture. At the border between the sidewalk and the field-like interior, they’ve heightened the presence of the past. Most of the block, a fence employing modern renditions of African motifs “makes strange” the border. It’s weird and memorable.

At the corner, the new building acts like a thickened version of the fence: it’s a border you inhabit, a threshold. The architecture mediates between Brooklyn and Weeksville as much as the exhibits within. For example, the doorway stands off-center in a big frame, positioned so that you notice where it is. It’s where a lost road crossed the threshold. Visitors are retracing the footsteps of Weeksville residents.

The doorway remembers Hunterfly Road, but in a way that makes it useful today. It’s not preservation of the physical artifact, nor is it a pedantic reconstruction. It’s a historical reference with a totally practical form.

Strategy Two: Remember things differently

As a parallel, think about the road’s name: “Hunterfly” comes from the early modern dutch “Aan der vly” meaning “to the swamp,” since it was an old Indian trail to the woody marshes around Jamaica Bay. As Dutch influence faded, the name was reinterpreted with plausible English words. Almost forgotten, in the name is now an artifact.

There name was re-rationalized to serve its purpose, losing its specific meaning but retaining its overall form. In design, the method is similar. Where a building is not worth preserving, or where archaeological evidence is disturbed, new construction can reference a lost presence. In fact, it can often be more accessible than a pure historical site.

Traditional cities already forget very productively: think of how pre-urban conditions persist in Tenleytown. Roads that are no longer dirt still follow donkey paths. Houses seem to face forgotten roads. A fire hydrant sits in the middle of a park. Presences of the past.

Caples Jefferson and landscape architect Elizabeth Kennedy call their recollection of Hunterfly Road a “ghost road,” I’ve touched on this idea before. In architectural academia, it’s called a “trace.” This term comes from ol’ Derrida, who argued that ideas unintentionally reference other ideas, since all concepts are defined through an infinite series of negations. (So the theory goes.) If you forget the narrow definition, you can start to see its application in the physical world.

The donkey paths are traces of old economic needs. The road is there, as opposed to somewhere else, for a cart that passed between two houses, until property changed hands a few hundred times and new uses gave the road a new significance in a non-linear process. The new residents of Kings County traced “An der vly,” in their own language, much as they traced the road to their own needs. The peculiarities of Fort Reno contain George Dyer’s lot, the lot next door, Fort Pennsylvania, Reno Town, the grid, and the desire to get rid of Reno Town.

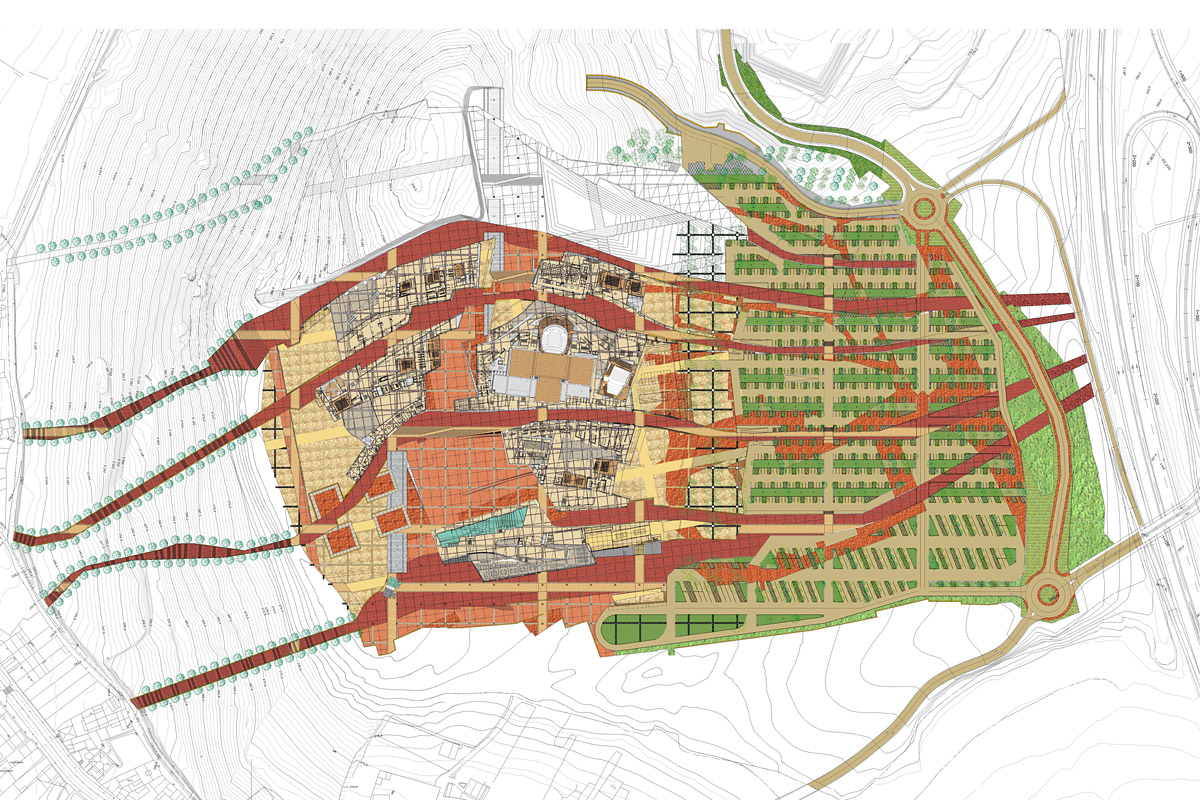

As an idea, “trace” came into architecture from Deconstruction through the writing of Peter Eisenman. Notorious for being simultaneously loose with concepts and literal with architecture, he tends to transliterate forms rather than reinterpret them, such as the hills, scallops, and pilgrimage paths at the City of Culture in Santiago de Compostela. This concept added new motivation to his theatrical formalism without adding external meaning.

Luckily, the idea got away from him. Meaning is the goal, and you have to build something to make the meaning apparent. Open-endedness is where projects that use traces well, like Weeksville diverge from ones that don’t.

What’s nice about the Weeksville project is that the trace appears in a few different ways: at the skewed doorways, as a wood path in the bus parking lot, a cut in a mound, a patch of native grass, and a paved surface near the houses. EKLA employed a mix of very functional and very artistic forms, and that fluidity guarantees that you never get it confused with the actual historic buildings.

In Tenleytown and Fort Reno, there’s much more green space and far fewer artifacts. The fort it totally lost. Only a little more survives from pre-urban Washington County. Often, what’s left is significantly changed or simply uninteresting on its own. Adding to the texture of place in Tenleytown will require re-imagining the contours of the past for future growth.

Strategy Three: Don’t be so sure

But, given that there are so few physical artifacts, how do you make it clear that something new is connecting to history. That’s a good question. I’d look to things that feel incomplete, like they contain potential that’s not quite realized. That’s what sort of interesting about it now; the little bits that don’t fit into the rest, letting you piece together the history.

So, like at Weeksville, build on what you have: odd roads, buildings sitting askew, foundations, fences, posts, cuts, berms. In more or less resolved forms, motifs that suggest an absence. The project might start with a program of contemporary uses. Then, the design process would discover compatible evocations. A rotated field, a path that looks strange, a jag in a building. The open-endedness of traces, allows the design to slip from one memory to the next, and back out.

The slipperiness is filled in by the imagination of the people inhabiting the park. A good trace becomes more than just a documentation, it creates a tension between between actual things and virtual presences. A good evocation, like the Dalva memorial stimulates the imagination and requires people to interpret the site, keeping the memory alive. I’ve found that references that are too clear about their truthfulness don’t make great architecture.

It’s easy to see how the false certainty you see at, say, Colonial Williamsburg can be soul-deadening. But the other kind of certainty is less criticized by architects: archaeological precision. Bare signs like VSBA’s Franklin Ghost House in Philadelphia points so much at how it’s not the real thing, there’s little room for imagining what it was. We all get it; all that’s left is irony.

For another bad example, take MVRDV’s entry into the Zaryadye Park competition. Zaryadye is a former neighborhood in between Red Square and the Moscow River. During the Soviet period, Stalin wiped it out to build the eighth vysotka, but instead it became the Hotel Rossiya, a mix of ugliness and poor craftsmanship with a way that really says “Khrushchev.” After an abortive attempt to make it a mixed-use development, the government decided to build a big park.

So MVRDV mapped all of the footprints of former and unbuilt parts of the site. With the exception of the Hotel Rossiya, each building gets the same treatment, a boxy extrusion. The old hotel becomes a moat, but every other imprint appears in a thin layer. It’s shallow and unedited. It doesn’t find affinities between the trace and present uses. A trace also appears in Turenscape’s proposal more selectively, but still not in a way that engages with ongoing needs.

To me, the big problem is that, like the Ghost House, it’s the safest statement of a former presence. There’s no argument brought up by the way the featureless plans are brought up. It’s merely an accounting of different plans for that area. It’s certain about what was there, but doesn’t venture into the uncertain ground of what each one of those layers means, how they are a product of the city’s values, and how the unbuilt projects have affected Moscow’s development.

There are many ways to connect a neighborhood to its past. Preservation is only one, and in Tenleytown it’s the worst method. A new consciousness about climate change and growth points to intensive use of the land around transit sites. Saving mutilated trinkets like Dunblane gets in the way of affordability and ease of transportation. The architectural idea of tracing history is a way to have it all and more.

For parks, this means they need to be more than grassy patches. Contemporary enjoyment can respect the past. In fact, I think that a well-concieved trace can fulfill the National Park Service’s mission of interpreting sites. There is no reason why design, recreation, and history cannot coexist at Fort Reno. All it requires is a little imagination.